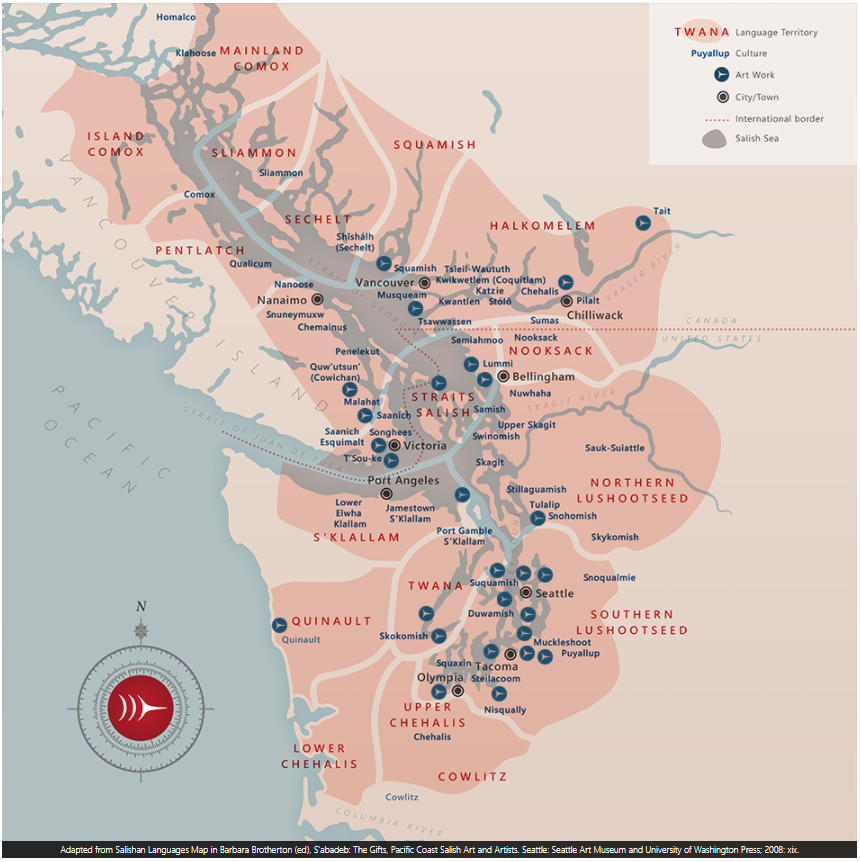

SR3 had a successful start to their new collaborative project with the North Gulf Oceanic Society to assess the health of fish-eating Resident killer whales in the Northern Gulf of Alaska.

A week-long field project was conducted in late May in the coastal waters around the Kenai Fjords, and the team was able to fly a remotely controlled octocopter drone to collect photogrammetry images of 32 individual whales from two Alaska Resident pods (AD8 and AK2), including four new calves.

Size and body condition of these abundant and increasing Alaska Residents will be compared to the endangered and declining Southern Resident killer whales to generate health benchmarks to facilitate recovery monitoring. The team will head back up to Alaska in August for a two-week field project in the spectacular Prince William Sound.

Aerial images of two female-calf pairs from the AK2 pod of the Alaska Resident killer whale population. Images were collected non-invasively using a remotely-controlled drone flown at >100ft over the whales under NMFS research permit #20341. Photo by Holly Fearnbach (SR3) and John Durban (North Gulf Ocean Society).