By Kate Hruby, Communications Specialist

An animal husbandry staff feeds the harbor porpoise a fish under the water, while he is stabilized in his flotation sling.

Every patient that we treat arrives with a unique story, contributing valuable insights into the health of our shared oceans. By rescuing and caring for sick and injured animals, we deepen our understanding of the threats and challenges they face in the wild.

SR3’s veterinarian, Dr. Michelle Rivard, takes an ultrasound of the harbor porpoise on the first night of his care.

For this harbor porpoise, his story started in South Puget Sound where he was found struggling in shallow water. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife responded to the scene, determined that he would not survive if left there, and transported him to SR3’s Rescue Center for further assessment. When he arrived, our immediate focus was on providing medical care to stabilize his condition, and conducting diagnostics such as bloodwork and ultrasound to thoroughly assess his health.

Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) are challenging to rehabilitate due to their size, animal husbandry needs, and potential health issues that could be acquired during stranding or transport. This animal remained responsive throughout transport, and his clinical condition stabilized after he was provided initial supportive care. Based on this first medical assessment, we did not see a need for immediate humane euthanasia, as is so often the case for this species, and instead elected to continue rehabilitation.

Cetaceans are also very time-intensive animals to care for; this harbor porpoise required someone in the pool with him at all times to monitor his behavior, guide his movements, and keep him comfortable in the sling we placed him in for flotation assistance. Our volunteers rose to the occasion, and we also reached out for support from many veterinarians and marine mammal rehabilitation staff along the West Coast. Despite this patient's extensive needs, we were able to maintain 24-hour care with the help of this incredible community.

A volunteer walks in a circle in the pool to give the porpoise constant movement.

While caring for him, it was clear that he was having some kind of neurologic issue, as he was unable to swim or stay upright on his own. To determine what may be the underlying cause of his condition, we began extensive diagnostic testing that included bloodwork, fecal samples, blow hole swabs, radiographs, ultrasounds and endoscopy. These tests showed us that he was free from many of the infectious diseases that we screened for, though he did have a moderate parasite burden. Initial radiographs were indicative of a past trauma or ongoing inflammation associated with his skull and nasal passages.

As we continued to treat him, we noticed some small improvement in his overall condition; he began eating on his own again and his strength increased. On his twelfth day in care, with his condition stabilized, we began to treat him for his parasitic infection by administering a deworming medication.

Later that evening, he began showing signs of stress and had a harder time eating than he had over the past few days. Guessing that his stress was due to the die off of the parasites, we gave him medication to help his body deal with that issue. Unfortunately, a couple of hours later, he began to have a seizure. When we were unable to control the seizures with medication, we decided humane euthanasia was in his best interest. Because he rapidly declined shortly after treatment of the parasites, it tracked closely with our concerns that parasites compromised his skull and normal neurologic functions. Due to the heavy parasite load, it became apparent that this was a condition we would not have been able to treat.

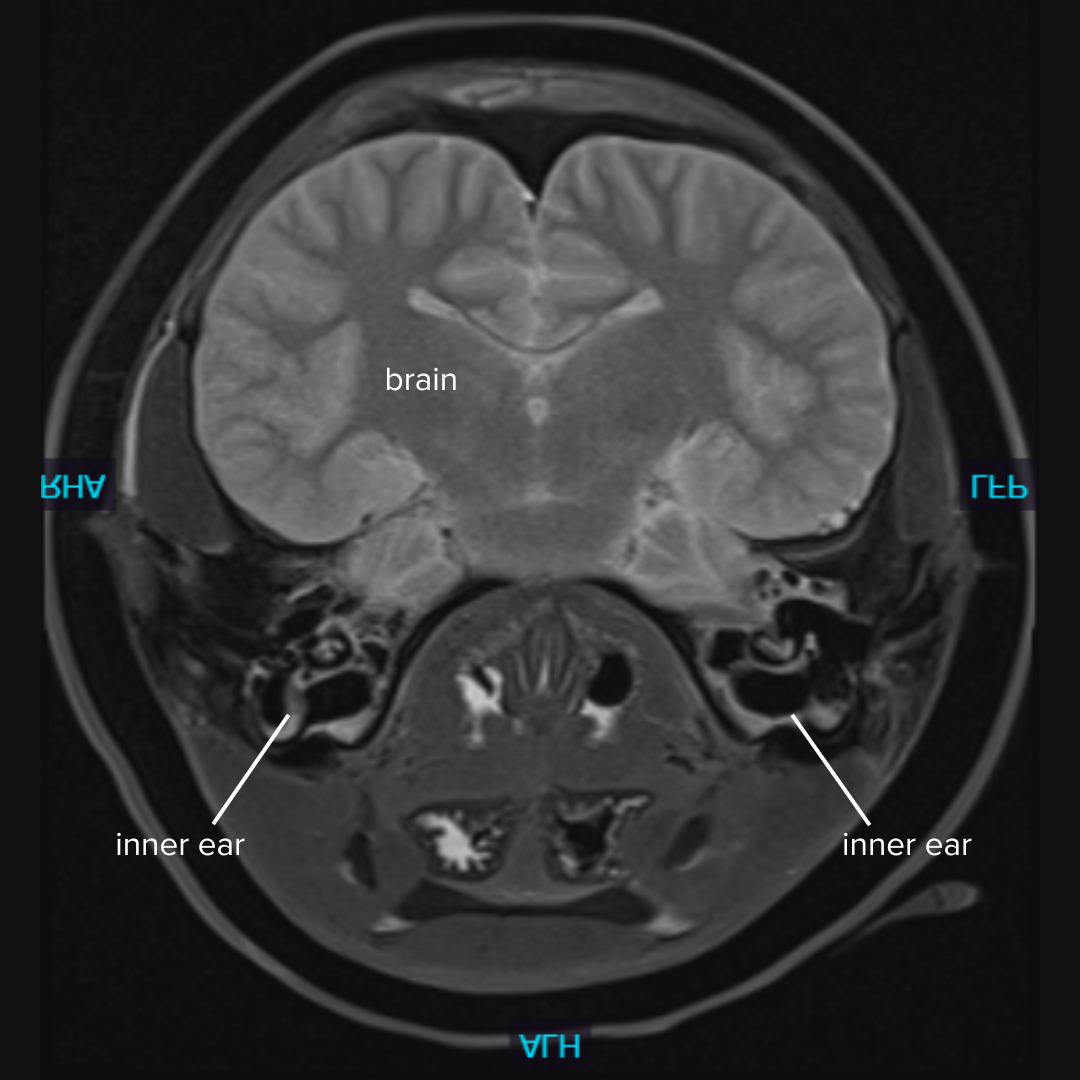

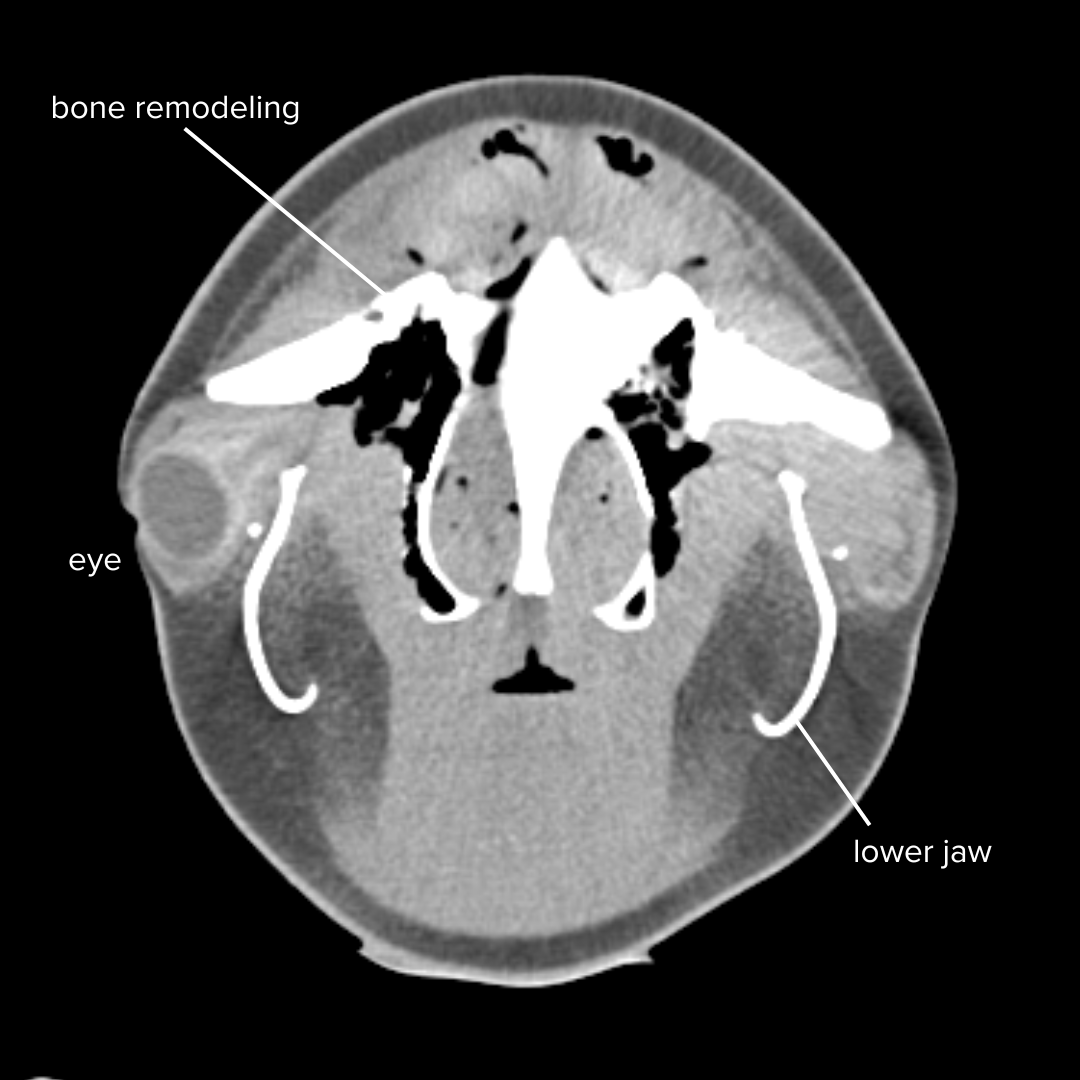

As with any of our patients that do not survive, our next steps were to try to learn as much as we could about what may have caused his stranding and his medical condition. CT scans and an MRI of his skull and brain were taken post-mortem, and a necropsy was performed to give us a clearer picture of what he might have been struggling with. We discovered he had a parasite that, while normally residing in the nose of a harbor porpoise, had migrated into his inner ear. This caused remodeling of bony structures of the skull and inflammation of the nasal passages, sinuses, and cranial nerves. The amount and location of parasites that were found explains his lack of balance in the water and other neurologic issues we observed.

While this patient didn’t make it, his journey has provided SR3 staff and volunteers with invaluable knowledge about the care of harbor porpoises and other small cetaceans. As additional test results come back, they will contribute to broader scientific knowledge of this species and could impact future conservation efforts. SR3 continues to stand ready and is more prepared than ever for the next stranded porpoise or dolphin who needs care.